What is the I-2 Newcastle disease vaccine?

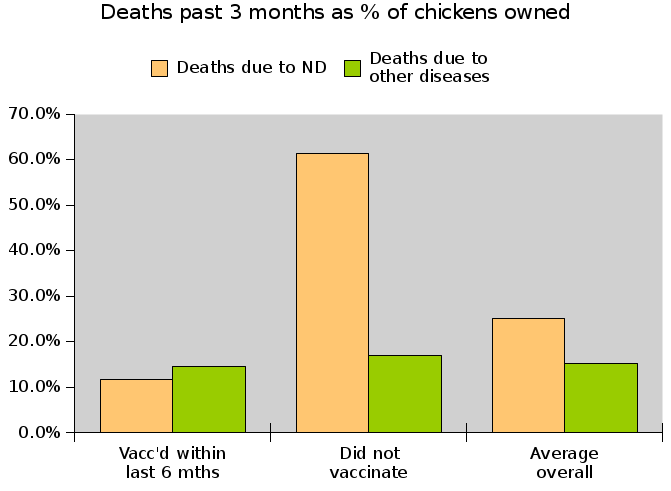

Newcastle disease has long been recognised as one of the major diseases of poultry. It was first recognised as a distinct disease in the 1920s and since then has been found virtually world wide. There is no effective treatment, so vaccination programs have long been a critical element in the prevention of this disease.

Given the parallel rapid developments in virology and the commercial poultry industries since the 1950s, it is not surprising that Newcastle disease (ND) vaccines have been developed with commercial enterprises as a top priority, a key market if you like. As a result, there are today a wide range of ND vaccines, well suited for commercial chickens but not so suitable for use in village chickens. Fortunately, this gap was recognised by Australian aid agencies as early as the mid 1980s and a concerted program of research and development was begun.

The late Dr Peter Spradbrow, whose team pioneered research into Newcastle disease and the development of vaccines which were suited to the village environment.

It wasn't easy. Village chicken flocks are generally small, largely unrestricted, and are often found in areas where facilities such as refrigeration and transport are not accessible and technical knowledge is limited. In a commercial poultry farm, uptake of vaccine could easily be enforced through applying vaccine via sprays, water or feed. Village chickens however, were easily able to evade such techniques.

In the 1990s, Dr Peter Spradbrow and his team measured the characteristics of various Newcastle disease viruses, which had been found in Australia. He measured things like how tolerant they were to being held at room temperature, whether they made chickens sick, and how much they provoked immunity. On the basis of these results, the I-2 virus was found to be an ideal candidate for a vaccine. It was efficacious in provoking immunity, it was avirulent, and very significantly, it was rather more thermo-tolerant than most strains.

Spradbrow and his colleagues were perhaps fortunate to receive prolonged financial support from the Australian Council for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) which, particularly through the vision of its then Director Dr John Copland, maintained a concerted program aimed at improving Newcastle disease vaccines for village poultry and the mechanisms to ensure their delivery to the smallholder farmers who needed them. Another key player in this work in East Africa was Dr Robyn Alders part of whose story we have told elsewhere.

It has been an amazing journey. Australian development agencies top the international arena in terms of their persevering support for Newcastle disease control in village chickens.

The result is that today, a number of vaccine production units for the I-2 vaccine have been established and/or supported in countries in Africa with a view to enabling vaccination of rural poultry which would otherwise simply have been left to die. The work of extending this model to the huge numbers of communities yet to establish their vaccination programs is a vital part of the work of institutions like Kyeema and the Rural Poultry Centre in Malawi.

Pat Boland

28 February 2018